Photography Redux or the Randomness of a Monday Morning

I am always impressed by those who have photographic vision, though I am always at some pains to grasp exactly what it is about that kind of seeing, if it exists at all. Photographic seeing if it exists allows a photographer to capture a moment in history. That captured moment can entertain us, horrify us or educate and enlighten us. The more talented the photographer, the more we are made aware of the world around us. Photographic vision not only allows us to see more of the world, but allows us to see through different eyes. Henri Cartier-Bresson whose work spanned the 20th century, Margaret Bourke-White who worked primarily before 1950 and Cindy Sherman, a currently living and active artist are three photographers, who capture what I appreciate about photographic vision.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was present at many important events of the 20th century, from the Spanish Civil War, to the German occupation of France, the partition of India and the Chinese revolution, Cartier-Bresson was a photojournalist of the highest rank. Throughout most of his photographic career there was one constant, his Leica 35mm. The French novelist and critic Andre Pieyre de Mandiargues once said that Cartier-Bresson used his Leica "rather as the Surrealists tried to use automatic writing: as a window that leaves one permanently open for visitations of the unconscious and the unpredictable" (Ebony 2004, 188). Cartier-Bresson in his most famous collection The Decisive Moment, sought to capture life in its singular essence, the living essence of life. In his own words he offers upon discovering the Leica, "It became the extension of my eye, and I have never been separated from it since I found it…determined to "trap" life-to preserve life in the act of living" (Sontag 1973, 185). This act of trapping of capturing the decisive moment would become the hallmark of his photography. Cartier-Bresson's vision allowed him to capture those decisive moments where most of us would only see the mundane. Nietzsche suggests that, "To experience a thing as beautiful means to experience it necessarily wrongly" (Sontag 1973, 184). Cartier-Bresson understanding of the world often flew in the face of such a dour supposition.

One photograph that uniquely and elegantly captures that moment in which one's attention is immediately and intensely drawn to the beautiful out of the mundane is Cartier-Bresson's Behind the Gare St. Lazare. On the face of it we see a man running across a large puddle behind what is a train terminal in Paris. However, a formal analysis of the image reveals delightful similarities that would otherwise be missed in the instant (Savedoff 1997, 208-209). Initially, the fortuitous timing of the picture as the man has just stepped off the ladder and has not broken the mirror-like surface of the water. Secondly, the slats of the ladder match the repeated metallic bars of the fence behind him. The poster on the wall features an image of a dancer leaping recapitulating the main action of the photo. Finally, the ripples in the puddle repeat the circular elements peeking out from the surface of the water. The schematization of the moment in time reveals an aesthetic symmetry between the environment and action, between the animate and inanimate, which is awe-inspiring and elegantly beautiful. Some might complain that the fortuitousness of such an image is perhaps too fortuitous, and indeed such a complaint might be legitimate. We are apt, when it comes to photos, to lend our confidence too quickly in its veracity (Savedoff 1997, 207). This easily given confidence evidenced by the mischievous appeal of "photoshopped" pictures, in which images are digitally altered in such a way as to appear legitimate. In a painting, the repetition that is envisioned in Cartier-Bresson's photo would seem contrived and strained. Because the nature of the photograph imputes an "as is" structure as it is an imaging of reality, which appears to us "as is," it is then the case that the repetition is unique, surprising and thus beautiful. It might be argued that the scene presented here is indeed contrived, but the "truth" of the moment is nevertheless maintained through Cartier-Bresson's unique photographic vision. As a world traveler Cartier-Bresson caught many decisive moments around the world, in doing so the viewers of his photographs became more aware of the subtlety and complexity of the world around them.

In another photograph of his travels, not the city streets of Paris but the remote mountain province of Kashmir on the border of India, Pakistan, and China we see four nomads watching out over the land. Kashmir is a heavily disputed territory and the sight of much bloodshed and violence. Though Cartier-Bresson was an insightful photojournalist, his photographic vision saw more than just that violence but the calm and peacefulness that could be found even in this war torn region. By presenting a view of Kashmir that did not consist primarily of violent upheaval, Cartier-Bresson offered a vision of social hope and social connection even in times of turmoil through an appeal to the senses.

In another photograph of his travels, not the city streets of Paris but the remote mountain province of Kashmir on the border of India, Pakistan, and China we see four nomads watching out over the land. Kashmir is a heavily disputed territory and the sight of much bloodshed and violence. Though Cartier-Bresson was an insightful photojournalist, his photographic vision saw more than just that violence but the calm and peacefulness that could be found even in this war torn region. By presenting a view of Kashmir that did not consist primarily of violent upheaval, Cartier-Bresson offered a vision of social hope and social connection even in times of turmoil through an appeal to the senses.

The next photographer's sight we will explore is that of Margaret Bourke-White. A photojournalist for the Luce Empire, her photos in Time, Life, and Fortune documented the world with a spectacular realism and emotional appeal. She was one of the first western photographers to witness the industrialization of the Soviet State, and one of the first women photographers to gain international fame and currency. Photojournalism as a medium of expressing information was brought into its golden age through her work. Though according to Barthes there is no code in the message of a photograph, a photograph can open up a moment in a way that a painting, or a story cannot. Sometimes, photographs can express an actuality that is behind the reality of daily life. Because reality has its own codes, that door to actuality can sometimes be closed off to us. The photographer as documenter and expositor can open those doors as Bourke-White explains, "Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open" (Fletcher 2007, 54).

The next photographer's sight we will explore is that of Margaret Bourke-White. A photojournalist for the Luce Empire, her photos in Time, Life, and Fortune documented the world with a spectacular realism and emotional appeal. She was one of the first western photographers to witness the industrialization of the Soviet State, and one of the first women photographers to gain international fame and currency. Photojournalism as a medium of expressing information was brought into its golden age through her work. Though according to Barthes there is no code in the message of a photograph, a photograph can open up a moment in a way that a painting, or a story cannot. Sometimes, photographs can express an actuality that is behind the reality of daily life. Because reality has its own codes, that door to actuality can sometimes be closed off to us. The photographer as documenter and expositor can open those doors as Bourke-White explains, "Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open" (Fletcher 2007, 54).

The depression of the pre-WWII era was devastating to many families and individuals, in the South and Midwest. A number of journalists and photographers collaborated to document this plight, to draw attention to those who would not otherwise get attention. Notably James Agee and Walker Evans work, Let us Now Praise Famous Men, and Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell's, You Have Seen Their Faces highlight in raw actuality the reality of the depression. One photo is particularly revelatory in this regard. "Louisville Flood Victims," juxtaposes to provocative effect a line of poor blacks huddled on a bread line beneath a billboard of a happy white family in their car and the banner: "World's Highest Standard of Living" (Fletcher 2007, 54). The exquisite acuteness of the message is intentional and thought provoking, and intentionally so. Much about photography is subtle and complex, Bourke-White's photo here is most definitely to the contrary. The contradistinction between the bright, shining, and oblivious faces of the family in the car coupled with the stern and dark faces of those waiting in line for bread underneath brings a poignant and legitimate note of irony to the phrase, "There's no way like the American Way." Other photos from You Have Seen Their Faces, such as this one of poor farmers in Yazoo City, Mississippi document the plight of the South during the Great Depression. Here we see their faces and realize that this group, this region of the United States had been forgotten. The text of the book reads, "It is that dogtown on the other side of the railroad tracks that smells so badly every time the wind changes. It is the Southern Extremity of America, the Empire of the Sun, the Cotton States; it is the Deep South, Down South; it is The South" (Caldwell and Bourke-White 1995, 1). By photographing the faces and people of the American South, Margaret Bourke-White made the rest of the country aware of the social circumstances of the hardest hit, forcing the American polity to see what they did want to see.

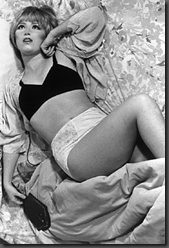

The final photographer whose vision reveals insight is that of Cindy Sherman. Cindy Sherman is a conceptual artist and photographer whose works often include herself installed in iconic and recognizable scenes. Her work tackles many subjects including ones of gender roles, identity, issues of sexual politics and the "gaze." As such, much of her corpus is described as "feminist" in nature. However, this questionable label aside, the work of Cindy Sherman offers a vision of culture, which is unique insofar that it re-consumes images from other forms of popular media and then represents that re-consumption back onto itself. Thus philosophically, her photographic sight is a mirror of itself. In other words, her work offers a method of understanding how visual media understands itself, or for us how photography might see itself (Mauer 2005). In one of her most recognized set of works Untitled Film Stills, Sherman interposes herself in a number of non-specific yet eminently recognizable scenes. In Untitled Film Still #6, the twisted pin-up girl trope is played upon to slightly diabolical effect. The classic pin-up girl of the 40's and 50's should offer a sense of invitation and not seduction. There are specific bodily dimensions that must be offered, she must look ecstatic to be there. Here Sherman's proportions are intentionally photographed askew, by rotating the trunk of her body and arching her back her breast and hips look narrow and small instead of the canonical strictness associated with pin-ups. The clothes that she is wearing are clashing and mismatched and the facial expression is stultifying, she looks lifeless as a mannequin. The scene in general looks messy and disorganized, the sheets are wrinkled and the flower pattern is confusing. The overall rhetoric from the scene clashes inherently from what such a photograph would send as a message. Hence, the paradox of the photo offers a vision of the pin-up girl that is inherently accusatory, even morally imposing. Yet, despite this moral approbation, there is something undeniably attractive about the scene. Something that exudes a particular residue of sexuality despite the intentional mocking is evident.

The final photographer whose vision reveals insight is that of Cindy Sherman. Cindy Sherman is a conceptual artist and photographer whose works often include herself installed in iconic and recognizable scenes. Her work tackles many subjects including ones of gender roles, identity, issues of sexual politics and the "gaze." As such, much of her corpus is described as "feminist" in nature. However, this questionable label aside, the work of Cindy Sherman offers a vision of culture, which is unique insofar that it re-consumes images from other forms of popular media and then represents that re-consumption back onto itself. Thus philosophically, her photographic sight is a mirror of itself. In other words, her work offers a method of understanding how visual media understands itself, or for us how photography might see itself (Mauer 2005). In one of her most recognized set of works Untitled Film Stills, Sherman interposes herself in a number of non-specific yet eminently recognizable scenes. In Untitled Film Still #6, the twisted pin-up girl trope is played upon to slightly diabolical effect. The classic pin-up girl of the 40's and 50's should offer a sense of invitation and not seduction. There are specific bodily dimensions that must be offered, she must look ecstatic to be there. Here Sherman's proportions are intentionally photographed askew, by rotating the trunk of her body and arching her back her breast and hips look narrow and small instead of the canonical strictness associated with pin-ups. The clothes that she is wearing are clashing and mismatched and the facial expression is stultifying, she looks lifeless as a mannequin. The scene in general looks messy and disorganized, the sheets are wrinkled and the flower pattern is confusing. The overall rhetoric from the scene clashes inherently from what such a photograph would send as a message. Hence, the paradox of the photo offers a vision of the pin-up girl that is inherently accusatory, even morally imposing. Yet, despite this moral approbation, there is something undeniably attractive about the scene. Something that exudes a particular residue of sexuality despite the intentional mocking is evident.

Much of the work of Cindy Sherman mocks the kind of role that sex and sexual politics play in our society. At the end of the 1980's during the H.W. Bush administration, funding was cut to artists such as Andre Serrano, and photographer Robert Mapplethorpe who pushed the boundaries of social norms. The National Endowment for the Arts deemed that their work was morally licentious and corrupting and as such could not be publicly supported. In response, Cindy ![clip_image002[7]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/Averroes2006/SFX3OO80PSI/AAAAAAAAAKk/3KZepcSKago/clip_image002%5B7%5D_thumb%5B2%5D.jpg?imgmax=800) Sherman created a series of photographs in a collection entitled Sex. In this series of works, she photographed assembled parts of medical dummies in blatantly sexual positions and formations. How one chooses to understand these pictures, either as a pornographic depiction of the human body or as a random assemblage of plastic parts, it generates pointed queries about what is going to count as indecent expression and the philosophical underpinnings for those determinations. Though much of Sherman's work is both amusing and somewhat mischievous, it also asks very serious questions about issues of national morals and values and the role of art and photography to be mediums of free expression in a modern and ostensibly open liberal society. Cindy Sherman's photographic vision allows us to examine culture from a slightly askew perspective in order to fundamentally reassess its foundations.

Sherman created a series of photographs in a collection entitled Sex. In this series of works, she photographed assembled parts of medical dummies in blatantly sexual positions and formations. How one chooses to understand these pictures, either as a pornographic depiction of the human body or as a random assemblage of plastic parts, it generates pointed queries about what is going to count as indecent expression and the philosophical underpinnings for those determinations. Though much of Sherman's work is both amusing and somewhat mischievous, it also asks very serious questions about issues of national morals and values and the role of art and photography to be mediums of free expression in a modern and ostensibly open liberal society. Cindy Sherman's photographic vision allows us to examine culture from a slightly askew perspective in order to fundamentally reassess its foundations.

Through the work of Cartier-Bresson, Bourke-White, and Sherman it is possible to understanding the concept of photographic seeing as an educational process by which we can examine who we are as individuals, as a culture, as a nation, and as a world through eyes that are not our own. Such a process can be beautiful as in the work Cartier-Bresson, poignant and informative as in the photos of Bourke-White, or somewhat disturbing as often the work of Cindy Sherman is. Photographic seeing draws our attention in unexpected and unusual ways, and because of this we are all the more richer.

1 comment:

Love this post, Bresson is one of my favorites. We need to go shoot our own decisive moments sometime, like we always planned...

Post a Comment