From Puppies to Wolves

“La guerre est la guerre”

Randall Jarrell was an American confessional poet, a member of the so-called Fugitive Poets, during the middle of the 20th century. He has been described as, “perhaps the most skilled of American poets writing on the Second World War” (Hill 152). Indeed, the theme of the Second World War prefigures dominantly in many of his poems, including the three set for analysis in this paper: “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” “Losses,” and “Eighth Air Force.” As perhaps the most self-consciously psychoanalytical of the confessional poets, War itself offers a rich framework from which to construct a more universal theme, that of the loss of innocence (Willamson 283).

Randall Jarrell was an American confessional poet, a member of the so-called Fugitive Poets, during the middle of the 20th century. He has been described as, “perhaps the most skilled of American poets writing on the Second World War” (Hill 152). Indeed, the theme of the Second World War prefigures dominantly in many of his poems, including the three set for analysis in this paper: “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” “Losses,” and “Eighth Air Force.” As perhaps the most self-consciously psychoanalytical of the confessional poets, War itself offers a rich framework from which to construct a more universal theme, that of the loss of innocence (Willamson 283).

Jarrell in a number of his works adopts various voices, which may be related to his experiences during the war but at the same time distances himself as the particular Randall Jarrell in order to adopt an innocent or at least a voice not informed by the position of the omniscient author. This poetic strategy is described by one commentator as “the sweet uses of personae” (Beck 67). In a letter sent to a friend, we can gain significant insight to the sources of his personae:

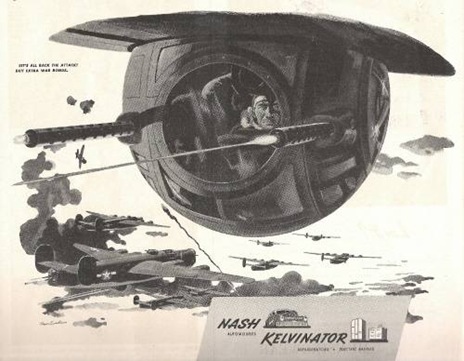

"The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner," resulted from his relief at not occupying that most vulnerable position in a combat plane. The composite voice in "Losses" intones, "In bombers named for girls, we burned / The cities we had learned about in school." Jarrell writes in the same letter that "your main feeling about the army, at first, is just that you can't believe it; it couldn't exist, and even if it could, you would have learned what it was like from all the books, and not a one gives you even an idea." The speaker of "Eighth Air Force," who judges himself along with the other "murderers" who sit around him playing pitch or trying to sleep, is but one remove from the flight instructor who describes to Tate how he would "sit up at night in the day room . . . writing poems, surrounded by people playing pool or writing home, or reading comic-strip magazines." (Beck 70)

As it relates to the loss of innocence we can see more specifically how this sweet use of personae is performed in his single most famous poem, “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” The poem begins mentioning “my mother” and then shortly thereafter using the word “belly,” implying an infantile or womb-like setting indicative of the settings of a child. The poem describes in indirect, uncomplicated detail the events that transpired. The loss of innocence is marked by the juxtaposition of the images “dream of life” and “nightmare fighters,” and the last line in which the author states his demise is both marked with a sense of bitterness at the casualness of his treatment, and resigned acceptance of the Gunner’s fate. The adoption of the innocent persona is also deployed in Jarrell’s poem “Losses.” The speakers attempt to offer an analogy as to how they died mentioning, aunts, pets and foreigners. This list at first is a bit eclectic and strange until the next line explains the selection, “When we left high school nothing else had died/For us to figure we had died like.” The list represents things that children, who are generally unfamiliar with death on a personal level, might have experienced as dying: a distant relative, clearly implying that these boys in their “new planes” were too young to have a parent die, a childhood pet, disappointing but commonplace, or someone they see on TV or hear about on the radio, too far away to really care about. The personal and tragic experience of their own death is an all too vivid and impactful event; such an event jolts them from their relatively quiescent relationship with death into the stark realities of war and suffering.

Another important rhetorical device employed by Jarrell in his work is to exploit the confusing, ambiguous and hectic nature of war as expressed by its inveigling and indirect language. Orwell notes this phenomenon of the fluidity and moral flexibility of war language:

In war and other times of political crisis, direct, forceful language becomes "transformed" and used in defense of the "indefensible." According to Orwell, political forces make use of the ambiguity and flexibility natural to language and metaphorical thought to further their political goals, making them more palatable to ordinary people through sterile terminology and euphemism. (Hill 153)

![clip_image002[5]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/Averroes2006/SFvK7PlhtRI/AAAAAAAAALA/uylXXlcccdE/clip_image002%5B5%5D_thumb%5B5%5D.jpg?imgmax=800) The use of military jargon is an effective means of obfuscating the blunt trauma of war, shielding innocence from its own crimes, obviously in one particular instance in “Eighth Air Force,” this language is betrayed when the speaker refers to himself and the other members of his troop as “murderers.” However, the presence of such language in his poetry foregrounds the awkwardness of military language, the narrative and rhetorical tension of the military phraseology is made apparent in the first two lines of “Losses”: “It was not dying, everybody died/It was not dying we had died before.” Dying is inherently personal and private, thus militaristically it does not, and cannot apply. Even the poems title, “Losses,” reinforces this sense of euphemism (Hill 154). It is not deaths or even casualties it’s…losses. As the poem progresses, however, the further exploitation of deflected discourse continuously builds the narrative tension in the work the “counting of scores,” as if it were just a game, the “turning into replacements” negating the individuality of one soldier or his death and thus annihilating a distinction between them. This tension maintains the innocent oblivion of the speaker until at the end, an overwhelming bitterness breaks the mood of the poem when the speaker asserts: “It was not dying --no, not ever dying.” Finally, the weight of the deflection becomes too much and the coming of age, the recognition of the reality of the situation becomes apparent as the speaker switches out of military code and style and questions, “Why are you dying…Why did I [my emphasis] die?” In remembering Tennyson’s mantra in “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” we can see why this questioning is a rhetorical break from the previous mode of the poem, to question one’s death, one’s dying, is indeed a violation of duty-“their’s is not to reason why, their’s is but to do and die.” This questioning not only marks a rhetorical break, but the putting aside of childlike concerns about the scores of missions, and girls and coming face-to-face with one’s own mortality. This individualization marks both the maturation of the speaker, as self-awareness is a hallmark of maturity, and the finality of the poem as for the first time the speaker refers to himself as “I,” in a manner highly uncharacteristic of “military speak.”

The use of military jargon is an effective means of obfuscating the blunt trauma of war, shielding innocence from its own crimes, obviously in one particular instance in “Eighth Air Force,” this language is betrayed when the speaker refers to himself and the other members of his troop as “murderers.” However, the presence of such language in his poetry foregrounds the awkwardness of military language, the narrative and rhetorical tension of the military phraseology is made apparent in the first two lines of “Losses”: “It was not dying, everybody died/It was not dying we had died before.” Dying is inherently personal and private, thus militaristically it does not, and cannot apply. Even the poems title, “Losses,” reinforces this sense of euphemism (Hill 154). It is not deaths or even casualties it’s…losses. As the poem progresses, however, the further exploitation of deflected discourse continuously builds the narrative tension in the work the “counting of scores,” as if it were just a game, the “turning into replacements” negating the individuality of one soldier or his death and thus annihilating a distinction between them. This tension maintains the innocent oblivion of the speaker until at the end, an overwhelming bitterness breaks the mood of the poem when the speaker asserts: “It was not dying --no, not ever dying.” Finally, the weight of the deflection becomes too much and the coming of age, the recognition of the reality of the situation becomes apparent as the speaker switches out of military code and style and questions, “Why are you dying…Why did I [my emphasis] die?” In remembering Tennyson’s mantra in “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” we can see why this questioning is a rhetorical break from the previous mode of the poem, to question one’s death, one’s dying, is indeed a violation of duty-“their’s is not to reason why, their’s is but to do and die.” This questioning not only marks a rhetorical break, but the putting aside of childlike concerns about the scores of missions, and girls and coming face-to-face with one’s own mortality. This individualization marks both the maturation of the speaker, as self-awareness is a hallmark of maturity, and the finality of the poem as for the first time the speaker refers to himself as “I,” in a manner highly uncharacteristic of “military speak.”

Another method of elucidating the ambiguity of war as a metaphor for the ambiguities of life is through the use of dream imagery, “the dream is a favorite motif of Jarrell's, both in his war poems and in his other poetry” (Calhoun 2). Dreams by their nature are confusing, and vague, but at the same time can be vividly intense, clarifying and extremely specific. The fog of war can often mimic the fog of adolescence, the whirlwind of emotions and hormones, the transition from childhood to young adulthood can be a confusing, intense and taxing period. Jarrell using dreams as a proxy for the fog is able to extend the metaphor from war to the battles in life. In “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” Jarrell performs an interesting reversal of the dream metaphor. Initially, the innocent womb-like existence of the gunner is the “dream of life” and he wakes up to a nightmare. Life is the tenuous dreamlike reality of the gunner, and reality is the distorted nightmare, the gunner literally wakes into death from his sleep of life (Cyr 94). This confusion is emblematic of the hectic and turbulent nature of war, which again is further emblematic of the confusion of life as one attempt to grapple with the realities therein. The inchoate distinctions between life and death, dream and reality are resolved in stark detail by the materialistic, “hard” description of being washed out of turret by a hose-there is no unclear dialogue, no deflected discourse in the action being described at the end of the poem. The dream trope is also utilized in “Eighth Air Force” in the final stanzas in attempt to display the difficulties in resolving the moral ambiguities that soldiers are faced with during war. In this poem the puppy has become the wolf, though admittedly through no fault of the puppy but through the routine of war as the speaker sighs, “Still this is how it is done.” Yet, the moment of moral clarity is brought through to its apotheosis through a dream. Jarrell in the line preceding the final stanza shows that the speaker has given into his moral responsibility invoking the phrase, “behold the man.” That phrase, Ecce homo, is used by Pontius Pilate when he is presented a scourged and thorn-crowned Jesus shortly before his Crucifixion. That religious imagery is maintained into the final stanza as Jarrell, “Using a complex allusion to the dream of Pontius Pilate's wife just prior to the crucifixion of Christ (Matthew 27:19), Jarrell's speaker obliquely refers to having "suffered, in a dream, because of him / many things" (Hill 159). It is many things suffered in the dream of that man “this last savior,” that transcends or at least clarifies the transition from puppy to wolf, from child to adult, from innocence to deep guilt. Jarrell does not exculpate the speaker, but neither does he condemn him when he comments that though men lie and wash their hands, in blood, he “finds no fault in this just man.” It is not just man that is responsible; it is the system of war, which manipulates individuals to becoming wolves, though these wolves are responsible, ultimate responsibility lies elsewhere.

Jarrell in the post-World War II saw the final primacy of the machine, its subjugation of all human feelings and intimations to the mindless "systems" of technology (Fowler 120-121). It is these “systems” that not only operate in wartime, but at all times, which pulls us along from sweet childhood to a more sour adulthood. It is at the teats of these systems where puppies are suckled into wolves.

No comments:

Post a Comment