Timeline

It is for those who come and those who have yet to, and it is for me, so that I may understand what they come for...

My idea was that when you do marry, you’re suddenly in all sorts of different relationships with other people, other institutions. All sorts of things come in and you’re obliged to interpret it and so forth, so it’s very much like the Brillo Box-Brillo Box structure.

In fact, as Danto assents “the whole thing’s different.” What is notably ironic about this assertion is that despite the totemic power that Danto assesses to Warhol’s creation: in After the End of Art and elsewhere Danto claims that it is exactly this piece, which marks the death knell of art (as a field of aesthetic creation), this art-object necessarily undermines the institutions which grant it that kind of radical ontology apart from brillo boxes. I wonder if marriage too, in its current (and perhaps always has been) fraught state, also undermines the very institutions which grant it its own status apart and seemingly above mere “couplehood.” A traditional explanation for the status of marriage might derive from the sacralization of the act within a religious frame, if such an explanation holds weight for marriage, this might say something about how we think of art (and artistic institutions like museums and schools). Many museums certainly carry an elegance, perhaps even an austerity that is cognate with what might be called the “church imaginary.” That is, the essentialization of the sum of ideas, representations and descriptions of a place of worship are often matched by what we might see entering a major art museum. The art-object placed within the museum-as-temple gains a sacred status, which is wholly apart from its mundane (profane) origins. Vermeer’s View of Delft isn’t just some boiled linseed oil, mixed with pine resin and pigments placed on top of stretched linen around a wood frame. It isn’t even just the product of an intelligent imagination; it is within the art-world discursive one of the finest examples of Dutch Renaissance veduta. That description only means something if that work is assigned as art. And one can only appreciate this meaning, if one appreciates the institution in which it is created. Brillo Boxes, if I understand it correctly wants to push this kind of appreciation, which borders on or is holy, to its absurd limit. Of course, we know thanks in part to some creative paraphrasing of Tertullian the intimate connection between absurdity and belief. If we think that marriage itself is only the kind of thing that can be marriage within the context of a set of institutions that provide its meaning, then we might understand (though not agree) with individuals who would quibble with those who would seek to participate in this ritual, whose sexual orientations might change the meaning of what it means to be married. That is, it would be anachronistically myopic (anachronistic given the significant work done in the wake of Heidegger and Nietzsche) to presume that meaning and being are somehow isolated, or furthermore, than meaning itself is created in a vacuum. Rather, if we recognize that the world is at all constructed, and if that construction if it is to be viable relies on some sense of intersubjective consensus or verifiability, then the prospect of gay marriage for those who have relied upon and trust a previously intersubjectively agreed upon (though perhaps always a contingent and tacit agreement) meaning, might represent a real (and for them unpalatable) change in the world, a change which not only affects all future marriages but marriage simpliciter. The danger (both rhetorically and politically) in such a philosophical outlook is fairly clear, and perhaps Danto did not intend to suggest that the parallel runs as far or as deep as I am making it out to be, but if Brillo Boxes represented the Death of Art, dare we say that marriage may encounter the same fate. My initial reaction is to cheer its apotheosis, but I understand that for some such a convulsion might be difficult perhaps even painful.

Mobility is not to be confused with freedom, but its converse...capture!

I was at : 50th, Tampa, FL 33617

"You want to be already sick of everything no one else has even heard of..."

From David Brook's Op-Ed Column in the August 7th, 2008 online edition of the New York TImes:

Dear Dr. Kierkegaard,

All my life I’ve been a successful pseudo-intellectual, sprinkling quotations from Kafka, Epictetus and Derrida into my conversations, impressing dates and making my friends feel mentally inferior. But over the last few years, it’s stopped working. People just look at me blankly. My artificially inflated self-esteem is on the wane. What happened?

Existential in Exeter

Ouch! It burns, it burns so deep.[Earnest fist-shaking] Mock me, will you Mr. Brooks! [/fist-shaking] For my part, I have worked exceptionally and obsessively hard to cultivate a face-saving level of ironic detachment (serious hours), and thus my self-esteem has suffered no undue inflation, artificial or otherwise. But where is this mythical dating pool-with their Grande Light Lattes and their copies of Finnegan's Wake and The Anti-Christ in tow? If you perchance occasion upon this and have determined the location of this private Elysian Starbucks(TM) of mine, please inform me of its whereabouts immediately. Epictetus? Really, do people have parts of the Enchiridion committed to memory so that they can bust it out at grad student soirees.

My acquired sense of disdain is reaching new heights, new heights I tell you!

Kafka, I think, in his Zurau Aphorisms, alerts us to the consequences of that afterthought DuBois supposed is lurking behind:

Kafka, I think, in his Zurau Aphorisms, alerts us to the consequences of that afterthought DuBois supposed is lurking behind:

"The animal twists the whip out of his master's grip and whips itself to become its own master-not knowing that this only a fantasy, produced by a new knot in the master's whiplash."-#29

"The Group and the Indie," Heather Boose Weiss (2004)

It has been many knots, perhaps now it is just knots. Moreover, is the animal exquisitely conscious of the fantasy of which he is the most industrious fabricator? If so, it seems we are always and already happy architects of our own nullification. A high price to pay for our existence. But indeed we can now conceive of Foucault's "law without the king," it is just the ungripped but heavily knotted whiplash. It suggests a canvas wherein a painter, stripped and bloodied, paints himself stripped and bloodied, but what shall he use for the pigment?

When Zora Neale Hurston died in 1960, she had been out of the public eye for some time with little of her work currently in publication. Largely through the efforts of Alice Walker and the influence of Walker's essay, "Looking for Zora," Hurston's oeuvre experienced a renaissance in the late 70's and 80's (Queen 52). Today her work is recognized as a seminal achievement of the Harlem Renaissance with her classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, required reading in high schools and in courses across multiple university departments. Her anthropological training and ethnographic work conducted under the advisement of the founder of American anthropology, Franz Boas, gave her the unique ability to identify, elucidate, and contextualize the specific timbre and tone of the African-American voice. However, much of her work encountered criticism, as what endeavored to be ethnographic authenticity was construed as a perpetuation of black stereotypes made pliant for her white audiences. This combined with her controversial political affiliations in the 1940's led to a rejection of her work for some time. One thematic element which operates consistently in her work is the role of women and her sensitivity to feminist concerns and issues of women's rights. Suffice it to say that many women in her novels and short stories play strong, consistent and even heroic roles and are often concern with other things than finding a husband or having children.

When Zora Neale Hurston died in 1960, she had been out of the public eye for some time with little of her work currently in publication. Largely through the efforts of Alice Walker and the influence of Walker's essay, "Looking for Zora," Hurston's oeuvre experienced a renaissance in the late 70's and 80's (Queen 52). Today her work is recognized as a seminal achievement of the Harlem Renaissance with her classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, required reading in high schools and in courses across multiple university departments. Her anthropological training and ethnographic work conducted under the advisement of the founder of American anthropology, Franz Boas, gave her the unique ability to identify, elucidate, and contextualize the specific timbre and tone of the African-American voice. However, much of her work encountered criticism, as what endeavored to be ethnographic authenticity was construed as a perpetuation of black stereotypes made pliant for her white audiences. This combined with her controversial political affiliations in the 1940's led to a rejection of her work for some time. One thematic element which operates consistently in her work is the role of women and her sensitivity to feminist concerns and issues of women's rights. Suffice it to say that many women in her novels and short stories play strong, consistent and even heroic roles and are often concern with other things than finding a husband or having children.

The political discourse of the mainstream of the Harlem Renaissance was centered on rebelling against the perceived stereotypes of African-Americans in the era of Jim Crow. "Negro Art," as suggested by W.E.B. DuBois and others, should seek to advance the situation of African-Americans (McKnight 83). Hurston's contrarian stance was not popular with other members of the Renaissance. Richard Wright accused her of nothing less than a kind of literary "Uncle Tomism" when he said that her work, "exploits that phase of Negro life which is 'quaint', the phase which evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the 'superior' race'" (McKnight 83) This attack stems at least in part from her literary commitment to a faithful portrayal of rural "black dialect" in her work. This so-called "folk language" is grammatically unorthodox, phonologically and semantically loose, elliptical, highly metaphorical, patriarchal, and utilizes a language which is steeped in mythological allusions and superstitious references. A brief illustration of this can be seen early on in Their Eyes Were Watching God. In one scene, Pheoby Watson is urged to go home before dark by Mrs. Sumpkins who volunteers to walk her home and worries, "It's sort of duskin' down dark. De booger man might ketch yuh." Unconcerned about the "Boogie Man" Phoeby declines and quips that "mah husband tell me say no first class booger would have me" (Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God 4). Many members of the Renaissance took exception to this nostalgia for primitivism and complained that while Hurston's effort in Their Eyes was both poetic and humorous, it was tragically and detrimentally un-evolved. Other reviewers were ignorant or blind to this concern of primitivism and instead recognized the universal experiences of Hurston's characters and how she touched on the deeper levels of human existence (Heard 133). In Their Eyes many of the characters are concerned with issues of empowerment and self-fulfillment and their failure to reach it is emblematic of a human endeavor not just an African-American one.

The political discourse of the mainstream of the Harlem Renaissance was centered on rebelling against the perceived stereotypes of African-Americans in the era of Jim Crow. "Negro Art," as suggested by W.E.B. DuBois and others, should seek to advance the situation of African-Americans (McKnight 83). Hurston's contrarian stance was not popular with other members of the Renaissance. Richard Wright accused her of nothing less than a kind of literary "Uncle Tomism" when he said that her work, "exploits that phase of Negro life which is 'quaint', the phase which evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the 'superior' race'" (McKnight 83) This attack stems at least in part from her literary commitment to a faithful portrayal of rural "black dialect" in her work. This so-called "folk language" is grammatically unorthodox, phonologically and semantically loose, elliptical, highly metaphorical, patriarchal, and utilizes a language which is steeped in mythological allusions and superstitious references. A brief illustration of this can be seen early on in Their Eyes Were Watching God. In one scene, Pheoby Watson is urged to go home before dark by Mrs. Sumpkins who volunteers to walk her home and worries, "It's sort of duskin' down dark. De booger man might ketch yuh." Unconcerned about the "Boogie Man" Phoeby declines and quips that "mah husband tell me say no first class booger would have me" (Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God 4). Many members of the Renaissance took exception to this nostalgia for primitivism and complained that while Hurston's effort in Their Eyes was both poetic and humorous, it was tragically and detrimentally un-evolved. Other reviewers were ignorant or blind to this concern of primitivism and instead recognized the universal experiences of Hurston's characters and how she touched on the deeper levels of human existence (Heard 133). In Their Eyes many of the characters are concerned with issues of empowerment and self-fulfillment and their failure to reach it is emblematic of a human endeavor not just an African-American one.

Part of the vehement response from members of the Harlem Renaissance derives from the rightful supposition that Hurston's deployment of "Southern Negro dialect" was explicit, intentional and devastatingly well-researched, i.e. there was not an understandable yet innocent desire for authenticity, but instead an ideological and academic commitment which was present. Hurston's intellectual pedigree did not coexist peaceably with the emotionally charged political convictions of her peers. Her 1934 essay, "Characteristics of Negro Expression," gave a theoretical edge to the deployment of her controversial rhetorical strategies and as such she interposed herself as a cultural intermediary between two "cultures." As an emissary, her role as translator and transmitter of fin de siècle Black Culture was one she adopted with relish and style. Ironically, while many other members of the Harlem Renaissance participated in cultural apologetics, they saw her kerugma of Black Culture as blasphemous. In that essay she lays out in detail the poetics of "Negro Expression" focusing on the role of adornment, metaphor and dramatization in such speech (Hurston, Sweat 55-56).

It is unlikely that any serious discussion of Hurston's work can be conducted without a presentation of how she mediated the issues of race and race relations. This is perhaps an unfortunate commentary on the state of literary criticism, insofar as any analysis of "black" writers must consider how "blackness" plays in their work. Hurston does offer some interesting and rich insights into the nature of being "colored," insights that also run contrary to some of those reached by other members of the Harlem Renaissance. In "How it Feels to be Colored Me" a 1928 essay, first published in the literary magazine The World Tomorrow, Hurston makes a number of striking metaphorical allusions about being colored. One theme that the essay develops is the notion that "race" or being colored is something that is constructed and labeled, rather than being something that is inherently a part of a person. She remarks, "I remember the very day that I became colored" (Hurston, How it Feels to be Colored Me). By extension, there was a time she remembers when she was not colored, and this time was when she was in Eatonville, FL as a child. Her mythological beginnings in this town[1] are a source of deep remembrance as she references her time in this place often. In Eatonville she could be "Zora," the person she actually was behind her "coloredness." Though admittedly, despite the racism she must have felt, there is a sense of ambivalence even arrogance at the thought of race and racism. She taunts those who "belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all but about it." Furthermore, she claims that racism does not so much as bother her as it does astonish her, and in a clear bit of tongue-and-cheek bravado wonders, "How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It's beyond me" (Hurston, How it Feels to be Colored Me). Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison and other African-American writers impart a sense in their works of a deep and seething existential anger, one that is not easily shaken off or tossed away in the same breezy way that Hurston does in that particular essay.

colored" (Hurston, How it Feels to be Colored Me). By extension, there was a time she remembers when she was not colored, and this time was when she was in Eatonville, FL as a child. Her mythological beginnings in this town[1] are a source of deep remembrance as she references her time in this place often. In Eatonville she could be "Zora," the person she actually was behind her "coloredness." Though admittedly, despite the racism she must have felt, there is a sense of ambivalence even arrogance at the thought of race and racism. She taunts those who "belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all but about it." Furthermore, she claims that racism does not so much as bother her as it does astonish her, and in a clear bit of tongue-and-cheek bravado wonders, "How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It's beyond me" (Hurston, How it Feels to be Colored Me). Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison and other African-American writers impart a sense in their works of a deep and seething existential anger, one that is not easily shaken off or tossed away in the same breezy way that Hurston does in that particular essay.

Zora Neale Hurston did not use her fiction or non-fiction to advert some bluntly political agenda about "black empowerment" much to the dismay of some of her male counterparts in the Harlem Renaissance. Moreover, she regarded antagonistically such attempts to voice these feelings through explicit political sermonizing, as hinted at in her  first published novel, Jonah Gourd's Vine. The title is a biblical allusion from the Book of Jonah, in which God prepares a gourd for Jonah only to have it destroyed by a worm, also of God's preparation (Jonah 4:6-8). In one scene, after a sermon on the "race problem" is given a character is asked how she liked it-the character, Sister Boger responds incredulously, "Dat wasn't no sermon, dat was uh lecture" (Hurston, Jonah's Gourd Vine 159). When Hurston preached it was not in the model of religious proselytism or via the staging of excoriating political jeremiads but through a personal quest to seek the connections between identity and language, authentically and on her own terms (Cuiba 119).

first published novel, Jonah Gourd's Vine. The title is a biblical allusion from the Book of Jonah, in which God prepares a gourd for Jonah only to have it destroyed by a worm, also of God's preparation (Jonah 4:6-8). In one scene, after a sermon on the "race problem" is given a character is asked how she liked it-the character, Sister Boger responds incredulously, "Dat wasn't no sermon, dat was uh lecture" (Hurston, Jonah's Gourd Vine 159). When Hurston preached it was not in the model of religious proselytism or via the staging of excoriating political jeremiads but through a personal quest to seek the connections between identity and language, authentically and on her own terms (Cuiba 119).

All this is not to imply that Hurston was unfamiliar or failed to empathize with people who were disillusioned at the state of race relations at time, or more bluntly, who were angry with white people. It was and continues to be a divisive question that splits this nation, its communities, families and even its citizens' psyches. One of the best examples of this divisiveness is found in her short story, "Sweat." It tells of Delia a washerwoman and her abusive, misogynist husband Sykes. In many of her stories, it is the male characters that tend to give voice to this "black anger," while the female ones tend to take a more pragmatic, quiescent approach. At one point, Sykes chastises Delia for washing white people's clothing in his house, and accuses her of hypocrisy for doing so on Sunday. He yells, "You ain't nothing but a hypocrite. One of them amen-corner Christians--sing, whoop, and shout, then come home and wash white folks clothes on the Sabbath" (Hurston, Sweat 27). It is one thing to work on the Sabbath, a minor oversight as far modern society is concerned, it is an entirely other thing to be doing the "devil's dirty work." For Sykes, Delia's washing responsibilities can be seen as a literal realization of this metaphor. Though ultimately Hurston rejects the paradigm of the white man as devil being the primary structuring element of race relations in America; it is a sentiment that is well-understood by her and to a degree appreciated by her as well.

Zora Neale Hurston was the daughter of a Baptist preacher and was no doubt quite familiar with religious themes and the power that religion had to shape the lives of the people around her. It is clear from her writing that while she may not have adopted the same level of piety as that of her father, she did utilize religious imagery powerfully and effectively. In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, she devotes an entire chapter to "Religion." She explains that despite the prevalence of religious sentiment in her home, she questioned, from very early on, certain theological inconsistencies that she saw in the faith of her family. Though she claims that the questions "went to sleep" inside her as she grew, religion is a living, breathing character in her work that interacts with her other characters and hums rhapsodically in her narrative tune. Take for example in "Sweat," the initial scene a wedge is already driven between Sykes and Delia, when Sykes tricks Delia into thinking that a rattlesnake, which Delia is deathly afraid of, is beside her. As the story develops and their relationship deteriorates a false rattlesnake is replaced by an actual snake that Sykes managed to catch since it was lethargically full of frogs. As their marriage crumbles and as Bertha, Sykes's fat mistress, makes calls at their home-it is the snake that comes alive having properly digested its food. This is the biblical story of Adam and Eve writ small, though with one noteworthy twist, Adam brings Eve the troubles of the serpent. The image of the serpent and its theological implications are all the more talismanic as its progressive manifestation, from simulacra to total vivification, perversely pantomimes the sundering of her marriage.

What Hurston may have lacked in religious convicted was made up for by an abiding and compulsive desire to preach. The subjects of her homilies were often about the significance of language, not only something she had studied so hard to understand in her ethnographic studies in college, but something that she crafted so patiently and thoroughly in her  fiction. In Moses, Man of the Mountain, she portrays Moses as a man who brings liberation through language, language as liberation (Cuiba 120). In Their Eyes Were Watching God, Janie's grandmother explains that how she wanted to "preach about colored women sittin' on high, but they wasn't no pulpit for me." Without a pulpit that great sermon becomes the narrative of Janie's life, i.e. Hurston's novel, as her grandmother resolves, "Ah'd save de text for you" (Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God 16). Hurston's texts are in many respects are the sum of her sermons which were preached from the pulpit through the characters in her stories.

fiction. In Moses, Man of the Mountain, she portrays Moses as a man who brings liberation through language, language as liberation (Cuiba 120). In Their Eyes Were Watching God, Janie's grandmother explains that how she wanted to "preach about colored women sittin' on high, but they wasn't no pulpit for me." Without a pulpit that great sermon becomes the narrative of Janie's life, i.e. Hurston's novel, as her grandmother resolves, "Ah'd save de text for you" (Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God 16). Hurston's texts are in many respects are the sum of her sermons which were preached from the pulpit through the characters in her stories.

Zora Neale Hurston was a controversial and divisive figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Her work challenged many of the established desires of that group of intellectuals, and she challenged them with arrogance, stereotypically uncommon among black women of the pre-WWII era. Hurston dealt with a number of themes deftly in her fiction and non-fiction. It is a small stretch of the imagination to suggest that there were at least "three Hurstons" operating in her work. There is Professor Hurston, the anthropologist and ethnographer lecturing us on the importance of connecting with the authentic nature of a group's language and not sacrificing it in the name of political progress. There is "little Zora," the young girl from Eatonville, who did not know what it was like to be colored until she was placed in a world that would not let her forget; however, she is not overly perturbed by it and by making the best of her "colored me" in any way she could and she invites others to do the same. Finally, there is Reverend Hurston who recapitulates the rhapsodic, spiritual tone of her father during his sermons in order to advocate for the liberation of the spirit through a triumphant reconnection with language and its riches. According to biographers she spent the last years of her life working in a number of different positions in various areas of employment, though it is to wonder given her diverse literary occupations whether this situation suited her all the same.

[1] Some research suggests that despite her own claims that she was not born in Eatonville, FL but in Alabama and moved to Eatonville as a young girl.

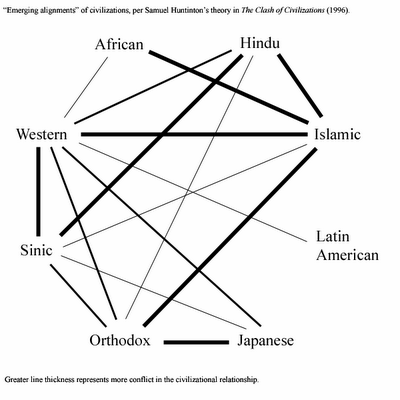

In hindsight, Samuel Huntington's now prophetic invocation of the "Clash of Civilizations," to explain the current global sociopolitical dynamic in contemporary society, can be seen to have a common intellectual experience with the narratives of cultural encounter by such authors as Graham Greene and Paul Bowles. Concomitantly, the current military quagmire in Iraq has reignited allusions to the Vietnam Conflict of four decades prior. The "fiction" of The Quiet American and The Spider's House speaks truth to our current situation more concretely than the grand ideological pronouncements of political scientists or historians. Both Greene and Bowles have a rather dour picture about the possibilities for reconciliation in a global ethical sense, and while we are not required to believe the conclusions they draw; it would behoove us to acknowledge the significant evidence they rally in their favor to support their outlook.

In hindsight, Samuel Huntington's now prophetic invocation of the "Clash of Civilizations," to explain the current global sociopolitical dynamic in contemporary society, can be seen to have a common intellectual experience with the narratives of cultural encounter by such authors as Graham Greene and Paul Bowles. Concomitantly, the current military quagmire in Iraq has reignited allusions to the Vietnam Conflict of four decades prior. The "fiction" of The Quiet American and The Spider's House speaks truth to our current situation more concretely than the grand ideological pronouncements of political scientists or historians. Both Greene and Bowles have a rather dour picture about the possibilities for reconciliation in a global ethical sense, and while we are not required to believe the conclusions they draw; it would behoove us to acknowledge the significant evidence they rally in their favor to support their outlook.

In the opening scene of The Quiet American, Thomas Fowler, the cynical and at times arrogantly self-assured British journalist, is waiting for Alden Pyle to return along with Phuong, a beautiful Vietnamese girl and one-time lover of Fowler. While being followed upstairs by Phuong, Fowler muses about the cleverly irksome things he could say to her but reconsiders and concludes, "Neither her English nor my French, would have been good enough to understand the irony" (11). One of the most if not the most fundamental aspect of cultural encounter is the deep barrier of language. Language in so many ways structures our reality, some philosophers such Martin Heidegger and Hans Gadamer offer that Language is the fundamental structure of reality. The failure to understand one another linguistically, often leads to the genuine failure of understanding one another in any capacity. Greene's novel constantly makes references to the difficulties of communication in foreign cultures. In another scene at the beginning of Chapter 3, Fowler is heading up the stairs to his flat after returning from the hospital and passes by the seemingly always present group of women gossiping about the neighborhood and wonders "what they might have told me if I had known their language” (115). Reaching the door of his flat, he hopes Phuong has received a message, if she was still there. His uncertainty is such because, "she wrote French with difficulty, and I couldn't read Vietnamese" (115) Greene is obviously committed to illustrating Fowler's lack of understanding and the problems, uncertainties and confusions that arise as a result.

Greene's repeated characterization of Fowler's ignorance reveals a second point about the nature of language in cultural encounter. As an experienced journalist in Indochina, Fowler by the start of the novel has been there approximately two years; one would think that he would have tried to learn some Annamese, that is the language of the Mon-Khmer people in Vietnam. It would obviously be an advantage as a reporter to be able to interview people in their native tongue, and of course to converse with the beautiful Phuong. Linguistic imperialism is often seen as a byproduct of the colonial situation. Fowler's ambivalence towards learning the Vietnamese language is a further bloc to cultural understanding and can be a source of cultural and racial tension. However, Fowler  is not totally oblivious to the damage that such a willful ignorance creates, after realizing that Phuong would not understand the irony of his jests- he notes, "I had no desire to hurt her or even myself."(11) The romantic nature of those comments aside, there is something pointed about Fowler's aversion that suggests that acting in this way not only hurts another person or another culture, but also hurts oneself in the end.

is not totally oblivious to the damage that such a willful ignorance creates, after realizing that Phuong would not understand the irony of his jests- he notes, "I had no desire to hurt her or even myself."(11) The romantic nature of those comments aside, there is something pointed about Fowler's aversion that suggests that acting in this way not only hurts another person or another culture, but also hurts oneself in the end.

Another feature of the colonial situation in cultural encounter is the essentializing tendency of foreign or colonized cultures. Cultural essentialism takes many forms, some with ironically good intentions, and others a byproduct of ignorance or self-assigned superiority. In Paul Bowles's The Spider's House, an expatriate American John Stenham living in Fez, Morocco, much like the narrator in Greene's novel, is a somewhat cynical and smug outsider. Unlike Fowler, Stenham is well-versed in the culture and language of Morocco and deeply admires it. While talking in a café to a rather judgmental British tourist, Polly, he tries to exculpate Polly's assessment that Moroccan culture is "primitive." This judgment was reached after he had previously explained the lack of windows in the café was due to the Moroccan conception of buildings as sheltering tents and thus to be really inside and feel safe there are no views to the outside. Stenham in response to Polly summation suggests, "They're not primitive at all. But they've held on to that and made it a part of their philosophy” (187) Essentializing the lack of windows to the philosophical survival of an old lodging system even in the defense against indictments of primitivism is still damaging to cultural and racial harmony. According to Stenham such "survivals" remain because of the "and then" nature of Moroccan society. What he offers is that because of the theological stipulation of Allah's constant intervention in daily affairs, Moroccans do not seek to find explanations or causes of things-as everything is, as it is, because Allah wills it. This is not like western culture according to Stenham, since Stenham is firmly a "because" culture. Polly, not done with her pronouncements, finds it all rather depressing. Stenham is quick to point out that there is nothing depressing about it; it is only depressing because of the Christian influence. He fears that Morocco in a few years will be nothing more than another European slum. Polly takes some offense to this suggesting that it is the French influence, which has brought railroads, streetlights, and much needed modernity. The philosophical and cultural conflict between the "East" and "West" illustrated by this exchange has been exceptionally well documented in recent years. Polly for her part is guilty of a kind of Orientalism, a thesis presented by Edward Said regarding the stereotyping and exoticizing of Eastern and Middle Eastern cultures. By suggesting that the west has made Morocco more modern has imposed a single, stifling view of what counts as modernity. The general rejection of cultures that do not fall in-line with this view is a common element of cultural encounter, one that generally speaking leads to conflict.

Alden Pyle, the committed anti-communist and titular "Quiet American" in Greene's novel is convinced that the Vietnamese do not want communism. Fowler, the cynic, quips "they want rice"(119) He also suggests what they really do not want is their "white skins around telling them what they want"(119). The racial tension between the Vietnamese and the French is palpable in Greene's novel. Just prior to the discussion about the Vietnamese desires, Fowler was taking Pyle's idol, York Harding, to task for devoting so much effort to things that do not exist, namely mental concepts such as God, Liberty, and Democracy. This discussion stands as a foil to the very sensory description of racial tension that  Greene provides subsequently. Fowler informs Pyle, "I like the buffaloes, they [referring to Vietnamese] don't like our smell, the smell of Europeans. And remember from a buffalo's point of view you are a European too” (119). Greene is insistent on pulling out these physical differences graphically, the white skins, the smell; even the buffaloes can tell who is who. It is the prerogative of modern scholarship that the concept of race is a social construction rather than set patterns of physiognomic difference. Nevertheless, tense conditions between various racial groups in this country and in others continue to persist along deeply sensed physical perceptions.

Greene provides subsequently. Fowler informs Pyle, "I like the buffaloes, they [referring to Vietnamese] don't like our smell, the smell of Europeans. And remember from a buffalo's point of view you are a European too” (119). Greene is insistent on pulling out these physical differences graphically, the white skins, the smell; even the buffaloes can tell who is who. It is the prerogative of modern scholarship that the concept of race is a social construction rather than set patterns of physiognomic difference. Nevertheless, tense conditions between various racial groups in this country and in others continue to persist along deeply sensed physical perceptions.

Bowles's work is equally cognizant of racial tension, but instead of defining it along explicitly physiological characteristics there is a typological component as well. In an episode involving Lee, a young woman whose "express desire was that all races and all individuals be equal,"(251) Stenham spots a boy who wades out into the middle of pool apparently to rescue a drowning insect. Stenham admits surprise that such a boy would do that, Lee's natural reaction is that the boy is likely kind-hearted to which Stenham responds, "I know but they're not” (250). Perplexed by such magnanimity, Stenham explores the boy's features for an explanation, "He could be Sicilian or Greek…but if he is [Moroccan] then I give up, Moroccan's just don't do things like that” (250). Idealistic Lee is indignant at this generalization and suggests that even if this act of kind-heartedness was unusual among a group of people generally, it does not mean any one particular individual will conform to this behavior. Bemused, Stenham replies, "But the whole point is they're not individuals in the sense you mean” (250). Bowles incisively and precisely exposes the thinking behind racial profiling. The whole point is that racial and intercultural strife evolves from a type of belief structure that does not recognize the universality of particulars. That is, it is easy to notice individuality and difference among members of the same race or culture; it becomes more difficult to discern the same kind of unique differences among the "Other." The naïve idealism which promotes the sort of belief that we are all the same underneath superficial differences is just as dangerous as the supposition that all others are "Other" in the same strange way. Regardless of the demographic categorization that one seeks to apply to a group of people, whether it is religion, race, ethnicity, or class-no demographic will act totally homogenously or hold the same set of beliefs.

In contemporary discussions, the ethical theories that deal specifically with the treatment of others in a global context fall under the heading of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism recognizes the likely insolvency of certain issues between individuals and groups of different cultural or racial background, while simultaneously holding that those differences are not necessarily insurmountable obstacles to reaching global amicability and respect. In these two novels the respective authors present the narrator as the cosmopolitan cynic, and transmit a deep sense of skepticism about the ability of humanity to accomplish anything resembling a cosmopolitan ideal. Moss, a friend of Stenham, believes that the problem with him is that he has "no faith in the human race"(211) On this count Thomas Fowler's disposition in Greene's novel is even more dolorous:

"Wouldn't we all do better not trying to understand, accepting the fact that no human being will ever understand another, not a wife a husband, a lover a mistress, nor a parent a child? Perhaps that's why men have invented God-a being capable of understanding"(72)

We are thrown back onto ourselves when the social and racial tensions of cultural encounters are exposed, since at the beginning of each encounter there is an "I," that is trying to make sense of "them," and realizing that perhaps there is no "us."

Shoot’em Up is a subtle critique on the preponderant narcissism of violence and sex that is ubiquitous in the movie industry by being painfully over-the-top. It intrepidly parries violence with violence, originating from two different discursive modes, by setting the traditional "shoot em up" tropes over and against the violence done towards good “film sense” utilizing ludicrous, and on one level, mindless camp. Clive Owen's performance is so awkwardly pultaceous that it exposes the internal paradox within the movie, which is further highlighted by his child-like obsession with carrots. The carrot is really a semiotic exchange, the value of which in this symbolic economy represents the trade-off between action movie spectacle and a desire for narrative and aesthetic cohesion. In other words, the heteronormative obsession with violence will only be sated (temporarily) at the cost of a more neutered and dispassionate appreciation of film craft. The deployment of a gendered discourse is made clearer through an analysis of the gun and carrot, which are the phallocentric images that drive and divide the movie towards its climax. The close-up of the no-man Smith biting a carrot has an eerily Freudian implication. Those implications become fully realized psychoanalytic themes as we are introduced to pregnant and lactating prostitutes, a symbolic merging of feminine archetypes irrupting unexpectedly (the sort of unexpectedness a prostitute might experience if she was, in fact, expecting) into the hyper-masculine universe of the film’s gun-toting milieu. Furthermore, these symbols swirl around the simulacra of a public figure, whose images on TV are phantasmagorical projections concealing the decaying body politic as metaphorically exhibited by the suffering/conniving politician. Of course, the revelation of the connection between the dying Senator and the infant offers a further nuance to the previously considered juxtapositions-that of the interplay between Thanatos and Eros. Also, Monica Bellucci is smokin’ hot in this.

Shoot’em Up is a subtle critique on the preponderant narcissism of violence and sex that is ubiquitous in the movie industry by being painfully over-the-top. It intrepidly parries violence with violence, originating from two different discursive modes, by setting the traditional "shoot em up" tropes over and against the violence done towards good “film sense” utilizing ludicrous, and on one level, mindless camp. Clive Owen's performance is so awkwardly pultaceous that it exposes the internal paradox within the movie, which is further highlighted by his child-like obsession with carrots. The carrot is really a semiotic exchange, the value of which in this symbolic economy represents the trade-off between action movie spectacle and a desire for narrative and aesthetic cohesion. In other words, the heteronormative obsession with violence will only be sated (temporarily) at the cost of a more neutered and dispassionate appreciation of film craft. The deployment of a gendered discourse is made clearer through an analysis of the gun and carrot, which are the phallocentric images that drive and divide the movie towards its climax. The close-up of the no-man Smith biting a carrot has an eerily Freudian implication. Those implications become fully realized psychoanalytic themes as we are introduced to pregnant and lactating prostitutes, a symbolic merging of feminine archetypes irrupting unexpectedly (the sort of unexpectedness a prostitute might experience if she was, in fact, expecting) into the hyper-masculine universe of the film’s gun-toting milieu. Furthermore, these symbols swirl around the simulacra of a public figure, whose images on TV are phantasmagorical projections concealing the decaying body politic as metaphorically exhibited by the suffering/conniving politician. Of course, the revelation of the connection between the dying Senator and the infant offers a further nuance to the previously considered juxtapositions-that of the interplay between Thanatos and Eros. Also, Monica Bellucci is smokin’ hot in this.

“La guerre est la guerre”

Randall Jarrell was an American confessional poet, a member of the so-called Fugitive Poets, during the middle of the 20th century. He has been described as, “perhaps the most skilled of American poets writing on the Second World War” (Hill 152). Indeed, the theme of the Second World War prefigures dominantly in many of his poems, including the three set for analysis in this paper: “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” “Losses,” and “Eighth Air Force.” As perhaps the most self-consciously psychoanalytical of the confessional poets, War itself offers a rich framework from which to construct a more universal theme, that of the loss of innocence (Willamson 283).

Randall Jarrell was an American confessional poet, a member of the so-called Fugitive Poets, during the middle of the 20th century. He has been described as, “perhaps the most skilled of American poets writing on the Second World War” (Hill 152). Indeed, the theme of the Second World War prefigures dominantly in many of his poems, including the three set for analysis in this paper: “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” “Losses,” and “Eighth Air Force.” As perhaps the most self-consciously psychoanalytical of the confessional poets, War itself offers a rich framework from which to construct a more universal theme, that of the loss of innocence (Willamson 283).

Jarrell in a number of his works adopts various voices, which may be related to his experiences during the war but at the same time distances himself as the particular Randall Jarrell in order to adopt an innocent or at least a voice not informed by the position of the omniscient author. This poetic strategy is described by one commentator as “the sweet uses of personae” (Beck 67). In a letter sent to a friend, we can gain significant insight to the sources of his personae:

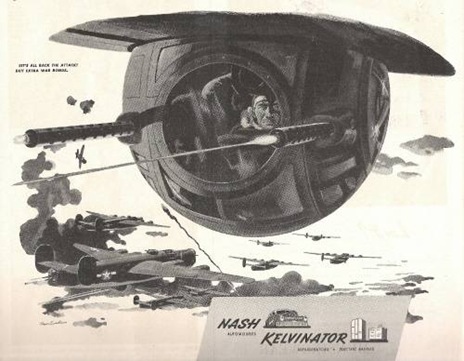

"The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner," resulted from his relief at not occupying that most vulnerable position in a combat plane. The composite voice in "Losses" intones, "In bombers named for girls, we burned / The cities we had learned about in school." Jarrell writes in the same letter that "your main feeling about the army, at first, is just that you can't believe it; it couldn't exist, and even if it could, you would have learned what it was like from all the books, and not a one gives you even an idea." The speaker of "Eighth Air Force," who judges himself along with the other "murderers" who sit around him playing pitch or trying to sleep, is but one remove from the flight instructor who describes to Tate how he would "sit up at night in the day room . . . writing poems, surrounded by people playing pool or writing home, or reading comic-strip magazines." (Beck 70)

As it relates to the loss of innocence we can see more specifically how this sweet use of personae is performed in his single most famous poem, “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” The poem begins mentioning “my mother” and then shortly thereafter using the word “belly,” implying an infantile or womb-like setting indicative of the settings of a child. The poem describes in indirect, uncomplicated detail the events that transpired. The loss of innocence is marked by the juxtaposition of the images “dream of life” and “nightmare fighters,” and the last line in which the author states his demise is both marked with a sense of bitterness at the casualness of his treatment, and resigned acceptance of the Gunner’s fate. The adoption of the innocent persona is also deployed in Jarrell’s poem “Losses.” The speakers attempt to offer an analogy as to how they died mentioning, aunts, pets and foreigners. This list at first is a bit eclectic and strange until the next line explains the selection, “When we left high school nothing else had died/For us to figure we had died like.” The list represents things that children, who are generally unfamiliar with death on a personal level, might have experienced as dying: a distant relative, clearly implying that these boys in their “new planes” were too young to have a parent die, a childhood pet, disappointing but commonplace, or someone they see on TV or hear about on the radio, too far away to really care about. The personal and tragic experience of their own death is an all too vivid and impactful event; such an event jolts them from their relatively quiescent relationship with death into the stark realities of war and suffering.

Another important rhetorical device employed by Jarrell in his work is to exploit the confusing, ambiguous and hectic nature of war as expressed by its inveigling and indirect language. Orwell notes this phenomenon of the fluidity and moral flexibility of war language:

In war and other times of political crisis, direct, forceful language becomes "transformed" and used in defense of the "indefensible." According to Orwell, political forces make use of the ambiguity and flexibility natural to language and metaphorical thought to further their political goals, making them more palatable to ordinary people through sterile terminology and euphemism. (Hill 153)

![clip_image002[5]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/Averroes2006/SFvK7PlhtRI/AAAAAAAAALA/uylXXlcccdE/clip_image002%5B5%5D_thumb%5B5%5D.jpg?imgmax=800) The use of military jargon is an effective means of obfuscating the blunt trauma of war, shielding innocence from its own crimes, obviously in one particular instance in “Eighth Air Force,” this language is betrayed when the speaker refers to himself and the other members of his troop as “murderers.” However, the presence of such language in his poetry foregrounds the awkwardness of military language, the narrative and rhetorical tension of the military phraseology is made apparent in the first two lines of “Losses”: “It was not dying, everybody died/It was not dying we had died before.” Dying is inherently personal and private, thus militaristically it does not, and cannot apply. Even the poems title, “Losses,” reinforces this sense of euphemism (Hill 154). It is not deaths or even casualties it’s…losses. As the poem progresses, however, the further exploitation of deflected discourse continuously builds the narrative tension in the work the “counting of scores,” as if it were just a game, the “turning into replacements” negating the individuality of one soldier or his death and thus annihilating a distinction between them. This tension maintains the innocent oblivion of the speaker until at the end, an overwhelming bitterness breaks the mood of the poem when the speaker asserts: “It was not dying --no, not ever dying.” Finally, the weight of the deflection becomes too much and the coming of age, the recognition of the reality of the situation becomes apparent as the speaker switches out of military code and style and questions, “Why are you dying…Why did I [my emphasis] die?” In remembering Tennyson’s mantra in “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” we can see why this questioning is a rhetorical break from the previous mode of the poem, to question one’s death, one’s dying, is indeed a violation of duty-“their’s is not to reason why, their’s is but to do and die.” This questioning not only marks a rhetorical break, but the putting aside of childlike concerns about the scores of missions, and girls and coming face-to-face with one’s own mortality. This individualization marks both the maturation of the speaker, as self-awareness is a hallmark of maturity, and the finality of the poem as for the first time the speaker refers to himself as “I,” in a manner highly uncharacteristic of “military speak.”

The use of military jargon is an effective means of obfuscating the blunt trauma of war, shielding innocence from its own crimes, obviously in one particular instance in “Eighth Air Force,” this language is betrayed when the speaker refers to himself and the other members of his troop as “murderers.” However, the presence of such language in his poetry foregrounds the awkwardness of military language, the narrative and rhetorical tension of the military phraseology is made apparent in the first two lines of “Losses”: “It was not dying, everybody died/It was not dying we had died before.” Dying is inherently personal and private, thus militaristically it does not, and cannot apply. Even the poems title, “Losses,” reinforces this sense of euphemism (Hill 154). It is not deaths or even casualties it’s…losses. As the poem progresses, however, the further exploitation of deflected discourse continuously builds the narrative tension in the work the “counting of scores,” as if it were just a game, the “turning into replacements” negating the individuality of one soldier or his death and thus annihilating a distinction between them. This tension maintains the innocent oblivion of the speaker until at the end, an overwhelming bitterness breaks the mood of the poem when the speaker asserts: “It was not dying --no, not ever dying.” Finally, the weight of the deflection becomes too much and the coming of age, the recognition of the reality of the situation becomes apparent as the speaker switches out of military code and style and questions, “Why are you dying…Why did I [my emphasis] die?” In remembering Tennyson’s mantra in “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” we can see why this questioning is a rhetorical break from the previous mode of the poem, to question one’s death, one’s dying, is indeed a violation of duty-“their’s is not to reason why, their’s is but to do and die.” This questioning not only marks a rhetorical break, but the putting aside of childlike concerns about the scores of missions, and girls and coming face-to-face with one’s own mortality. This individualization marks both the maturation of the speaker, as self-awareness is a hallmark of maturity, and the finality of the poem as for the first time the speaker refers to himself as “I,” in a manner highly uncharacteristic of “military speak.”

Another method of elucidating the ambiguity of war as a metaphor for the ambiguities of life is through the use of dream imagery, “the dream is a favorite motif of Jarrell's, both in his war poems and in his other poetry” (Calhoun 2). Dreams by their nature are confusing, and vague, but at the same time can be vividly intense, clarifying and extremely specific. The fog of war can often mimic the fog of adolescence, the whirlwind of emotions and hormones, the transition from childhood to young adulthood can be a confusing, intense and taxing period. Jarrell using dreams as a proxy for the fog is able to extend the metaphor from war to the battles in life. In “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” Jarrell performs an interesting reversal of the dream metaphor. Initially, the innocent womb-like existence of the gunner is the “dream of life” and he wakes up to a nightmare. Life is the tenuous dreamlike reality of the gunner, and reality is the distorted nightmare, the gunner literally wakes into death from his sleep of life (Cyr 94). This confusion is emblematic of the hectic and turbulent nature of war, which again is further emblematic of the confusion of life as one attempt to grapple with the realities therein. The inchoate distinctions between life and death, dream and reality are resolved in stark detail by the materialistic, “hard” description of being washed out of turret by a hose-there is no unclear dialogue, no deflected discourse in the action being described at the end of the poem. The dream trope is also utilized in “Eighth Air Force” in the final stanzas in attempt to display the difficulties in resolving the moral ambiguities that soldiers are faced with during war. In this poem the puppy has become the wolf, though admittedly through no fault of the puppy but through the routine of war as the speaker sighs, “Still this is how it is done.” Yet, the moment of moral clarity is brought through to its apotheosis through a dream. Jarrell in the line preceding the final stanza shows that the speaker has given into his moral responsibility invoking the phrase, “behold the man.” That phrase, Ecce homo, is used by Pontius Pilate when he is presented a scourged and thorn-crowned Jesus shortly before his Crucifixion. That religious imagery is maintained into the final stanza as Jarrell, “Using a complex allusion to the dream of Pontius Pilate's wife just prior to the crucifixion of Christ (Matthew 27:19), Jarrell's speaker obliquely refers to having "suffered, in a dream, because of him / many things" (Hill 159). It is many things suffered in the dream of that man “this last savior,” that transcends or at least clarifies the transition from puppy to wolf, from child to adult, from innocence to deep guilt. Jarrell does not exculpate the speaker, but neither does he condemn him when he comments that though men lie and wash their hands, in blood, he “finds no fault in this just man.” It is not just man that is responsible; it is the system of war, which manipulates individuals to becoming wolves, though these wolves are responsible, ultimate responsibility lies elsewhere.

Jarrell in the post-World War II saw the final primacy of the machine, its subjugation of all human feelings and intimations to the mindless "systems" of technology (Fowler 120-121). It is these “systems” that not only operate in wartime, but at all times, which pulls us along from sweet childhood to a more sour adulthood. It is at the teats of these systems where puppies are suckled into wolves.