Cultural Encounters of the Literary Kind

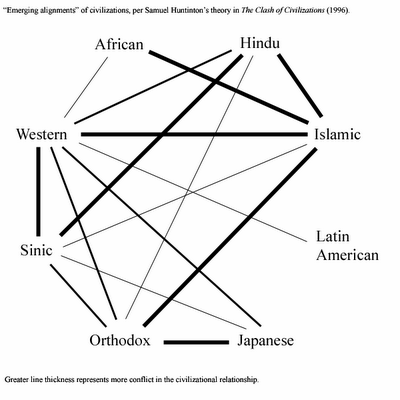

In hindsight, Samuel Huntington's now prophetic invocation of the "Clash of Civilizations," to explain the current global sociopolitical dynamic in contemporary society, can be seen to have a common intellectual experience with the narratives of cultural encounter by such authors as Graham Greene and Paul Bowles. Concomitantly, the current military quagmire in Iraq has reignited allusions to the Vietnam Conflict of four decades prior. The "fiction" of The Quiet American and The Spider's House speaks truth to our current situation more concretely than the grand ideological pronouncements of political scientists or historians. Both Greene and Bowles have a rather dour picture about the possibilities for reconciliation in a global ethical sense, and while we are not required to believe the conclusions they draw; it would behoove us to acknowledge the significant evidence they rally in their favor to support their outlook.

In hindsight, Samuel Huntington's now prophetic invocation of the "Clash of Civilizations," to explain the current global sociopolitical dynamic in contemporary society, can be seen to have a common intellectual experience with the narratives of cultural encounter by such authors as Graham Greene and Paul Bowles. Concomitantly, the current military quagmire in Iraq has reignited allusions to the Vietnam Conflict of four decades prior. The "fiction" of The Quiet American and The Spider's House speaks truth to our current situation more concretely than the grand ideological pronouncements of political scientists or historians. Both Greene and Bowles have a rather dour picture about the possibilities for reconciliation in a global ethical sense, and while we are not required to believe the conclusions they draw; it would behoove us to acknowledge the significant evidence they rally in their favor to support their outlook.

In the opening scene of The Quiet American, Thomas Fowler, the cynical and at times arrogantly self-assured British journalist, is waiting for Alden Pyle to return along with Phuong, a beautiful Vietnamese girl and one-time lover of Fowler. While being followed upstairs by Phuong, Fowler muses about the cleverly irksome things he could say to her but reconsiders and concludes, "Neither her English nor my French, would have been good enough to understand the irony" (11). One of the most if not the most fundamental aspect of cultural encounter is the deep barrier of language. Language in so many ways structures our reality, some philosophers such Martin Heidegger and Hans Gadamer offer that Language is the fundamental structure of reality. The failure to understand one another linguistically, often leads to the genuine failure of understanding one another in any capacity. Greene's novel constantly makes references to the difficulties of communication in foreign cultures. In another scene at the beginning of Chapter 3, Fowler is heading up the stairs to his flat after returning from the hospital and passes by the seemingly always present group of women gossiping about the neighborhood and wonders "what they might have told me if I had known their language” (115). Reaching the door of his flat, he hopes Phuong has received a message, if she was still there. His uncertainty is such because, "she wrote French with difficulty, and I couldn't read Vietnamese" (115) Greene is obviously committed to illustrating Fowler's lack of understanding and the problems, uncertainties and confusions that arise as a result.

Greene's repeated characterization of Fowler's ignorance reveals a second point about the nature of language in cultural encounter. As an experienced journalist in Indochina, Fowler by the start of the novel has been there approximately two years; one would think that he would have tried to learn some Annamese, that is the language of the Mon-Khmer people in Vietnam. It would obviously be an advantage as a reporter to be able to interview people in their native tongue, and of course to converse with the beautiful Phuong. Linguistic imperialism is often seen as a byproduct of the colonial situation. Fowler's ambivalence towards learning the Vietnamese language is a further bloc to cultural understanding and can be a source of cultural and racial tension. However, Fowler  is not totally oblivious to the damage that such a willful ignorance creates, after realizing that Phuong would not understand the irony of his jests- he notes, "I had no desire to hurt her or even myself."(11) The romantic nature of those comments aside, there is something pointed about Fowler's aversion that suggests that acting in this way not only hurts another person or another culture, but also hurts oneself in the end.

is not totally oblivious to the damage that such a willful ignorance creates, after realizing that Phuong would not understand the irony of his jests- he notes, "I had no desire to hurt her or even myself."(11) The romantic nature of those comments aside, there is something pointed about Fowler's aversion that suggests that acting in this way not only hurts another person or another culture, but also hurts oneself in the end.

Another feature of the colonial situation in cultural encounter is the essentializing tendency of foreign or colonized cultures. Cultural essentialism takes many forms, some with ironically good intentions, and others a byproduct of ignorance or self-assigned superiority. In Paul Bowles's The Spider's House, an expatriate American John Stenham living in Fez, Morocco, much like the narrator in Greene's novel, is a somewhat cynical and smug outsider. Unlike Fowler, Stenham is well-versed in the culture and language of Morocco and deeply admires it. While talking in a café to a rather judgmental British tourist, Polly, he tries to exculpate Polly's assessment that Moroccan culture is "primitive." This judgment was reached after he had previously explained the lack of windows in the café was due to the Moroccan conception of buildings as sheltering tents and thus to be really inside and feel safe there are no views to the outside. Stenham in response to Polly summation suggests, "They're not primitive at all. But they've held on to that and made it a part of their philosophy” (187) Essentializing the lack of windows to the philosophical survival of an old lodging system even in the defense against indictments of primitivism is still damaging to cultural and racial harmony. According to Stenham such "survivals" remain because of the "and then" nature of Moroccan society. What he offers is that because of the theological stipulation of Allah's constant intervention in daily affairs, Moroccans do not seek to find explanations or causes of things-as everything is, as it is, because Allah wills it. This is not like western culture according to Stenham, since Stenham is firmly a "because" culture. Polly, not done with her pronouncements, finds it all rather depressing. Stenham is quick to point out that there is nothing depressing about it; it is only depressing because of the Christian influence. He fears that Morocco in a few years will be nothing more than another European slum. Polly takes some offense to this suggesting that it is the French influence, which has brought railroads, streetlights, and much needed modernity. The philosophical and cultural conflict between the "East" and "West" illustrated by this exchange has been exceptionally well documented in recent years. Polly for her part is guilty of a kind of Orientalism, a thesis presented by Edward Said regarding the stereotyping and exoticizing of Eastern and Middle Eastern cultures. By suggesting that the west has made Morocco more modern has imposed a single, stifling view of what counts as modernity. The general rejection of cultures that do not fall in-line with this view is a common element of cultural encounter, one that generally speaking leads to conflict.

Alden Pyle, the committed anti-communist and titular "Quiet American" in Greene's novel is convinced that the Vietnamese do not want communism. Fowler, the cynic, quips "they want rice"(119) He also suggests what they really do not want is their "white skins around telling them what they want"(119). The racial tension between the Vietnamese and the French is palpable in Greene's novel. Just prior to the discussion about the Vietnamese desires, Fowler was taking Pyle's idol, York Harding, to task for devoting so much effort to things that do not exist, namely mental concepts such as God, Liberty, and Democracy. This discussion stands as a foil to the very sensory description of racial tension that  Greene provides subsequently. Fowler informs Pyle, "I like the buffaloes, they [referring to Vietnamese] don't like our smell, the smell of Europeans. And remember from a buffalo's point of view you are a European too” (119). Greene is insistent on pulling out these physical differences graphically, the white skins, the smell; even the buffaloes can tell who is who. It is the prerogative of modern scholarship that the concept of race is a social construction rather than set patterns of physiognomic difference. Nevertheless, tense conditions between various racial groups in this country and in others continue to persist along deeply sensed physical perceptions.

Greene provides subsequently. Fowler informs Pyle, "I like the buffaloes, they [referring to Vietnamese] don't like our smell, the smell of Europeans. And remember from a buffalo's point of view you are a European too” (119). Greene is insistent on pulling out these physical differences graphically, the white skins, the smell; even the buffaloes can tell who is who. It is the prerogative of modern scholarship that the concept of race is a social construction rather than set patterns of physiognomic difference. Nevertheless, tense conditions between various racial groups in this country and in others continue to persist along deeply sensed physical perceptions.

Bowles's work is equally cognizant of racial tension, but instead of defining it along explicitly physiological characteristics there is a typological component as well. In an episode involving Lee, a young woman whose "express desire was that all races and all individuals be equal,"(251) Stenham spots a boy who wades out into the middle of pool apparently to rescue a drowning insect. Stenham admits surprise that such a boy would do that, Lee's natural reaction is that the boy is likely kind-hearted to which Stenham responds, "I know but they're not” (250). Perplexed by such magnanimity, Stenham explores the boy's features for an explanation, "He could be Sicilian or Greek…but if he is [Moroccan] then I give up, Moroccan's just don't do things like that” (250). Idealistic Lee is indignant at this generalization and suggests that even if this act of kind-heartedness was unusual among a group of people generally, it does not mean any one particular individual will conform to this behavior. Bemused, Stenham replies, "But the whole point is they're not individuals in the sense you mean” (250). Bowles incisively and precisely exposes the thinking behind racial profiling. The whole point is that racial and intercultural strife evolves from a type of belief structure that does not recognize the universality of particulars. That is, it is easy to notice individuality and difference among members of the same race or culture; it becomes more difficult to discern the same kind of unique differences among the "Other." The naïve idealism which promotes the sort of belief that we are all the same underneath superficial differences is just as dangerous as the supposition that all others are "Other" in the same strange way. Regardless of the demographic categorization that one seeks to apply to a group of people, whether it is religion, race, ethnicity, or class-no demographic will act totally homogenously or hold the same set of beliefs.

In contemporary discussions, the ethical theories that deal specifically with the treatment of others in a global context fall under the heading of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism recognizes the likely insolvency of certain issues between individuals and groups of different cultural or racial background, while simultaneously holding that those differences are not necessarily insurmountable obstacles to reaching global amicability and respect. In these two novels the respective authors present the narrator as the cosmopolitan cynic, and transmit a deep sense of skepticism about the ability of humanity to accomplish anything resembling a cosmopolitan ideal. Moss, a friend of Stenham, believes that the problem with him is that he has "no faith in the human race"(211) On this count Thomas Fowler's disposition in Greene's novel is even more dolorous:

"Wouldn't we all do better not trying to understand, accepting the fact that no human being will ever understand another, not a wife a husband, a lover a mistress, nor a parent a child? Perhaps that's why men have invented God-a being capable of understanding"(72)

We are thrown back onto ourselves when the social and racial tensions of cultural encounters are exposed, since at the beginning of each encounter there is an "I," that is trying to make sense of "them," and realizing that perhaps there is no "us."

No comments:

Post a Comment