730 years ago a French Bishop by the name of Etienne Tempier, conducted what is known as the Condemnation of 1277. Though the specific motivations for this instance of condemnation are unresolved, some suggest that it was papal mandate while evidence suggests that the Pope though not disappointed by his all-to-eager Parisian Bishop's enthusiasm was surprised to learn of this rejection of some 219 various philosophical and theological treatises and propositions. In any event multiple members of the faculty of arts at the University of Paris were condemned and their works and thoughts were placed on the syllabus of errors. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the radical condemnation of the faculty can be seen as either one salvo in the battle between faith and reason, or Tempier's touchy temperament with the increasing rationalist or even populist currents growing in the university. He maintains that the philosophical fetishism which had been growing in academia created an atmosphere which supposed that, "...there were two contrary truths, and as if against the truth of Sacred Scripture, there is truth in the sayings of the condemned pagans." This is a reference to the hermeneutic strategy misunderstood as a metaphysical assumption, which is the doctrine of double-truth. The doctrine of double-truth states in its strong and never defended form that there are two truths, one revealed by Scripture and one revealed by man's reason. The other weaker form of the doctrine offers that an individual proposition can be analyzed from the standpoint of standard theological investigation, or from reasoned philosophical inquiry. I think the genuine fear was that intellectual effort, which was effective, persuasive and interesting was being performed outside the domain of the Church, and that this heretical trend if allowed to fester would infect society with a sickness, a sickness of independent thought.

Cross a few centuries, through the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Romantic reaction, the modern era, and the Postmodern and we arrive here, in the fascinating age of the Internet and the so-called Web 2.0. Where the free exchange of ideas, the rise of the Instapundits and YouTube-celebrities and the cacophonous blare of the blogosphere are delivered via the titter-tatter of keyboards in the wee hours of the morning. The fingers responsible for this titter-tatter, driven by inquisitiveness, caffeine (or perhaps harder fare) and apparently a Cult of Amateurishness. A recently published polemic, The Cult of the Amateur (Doubleday, $22.95) by Andrew Keen, is the latest in a series of relentless attacks on all the amoral evils and stifling discourses Web 2.0 has brought to culture. Of course, I am sure he anticipates the negative reaction he will receive from the citizens of the blogosphere; moreover, for those who are sympathetic to his position will see this as a vindication of his claims...insuring a vortex of non-falsifiability, Fantastic. I will not go into a review or point-by-point analysis of this book; however, if you go to Lessing Blog, you can see such a breakdown. What is interesting about his interpretation is that he claims the book is self-referential satire laced with a great deal of irony and hence should be considered a fantastic boon to the bloggers of the world instead of a call to arms. I will leave this an open question.

Mr. Keen (ironic or not) is not alone in his condemnation. Nicholas Carr over at RoughType, seems to have a special place of hatred for Wikipedia. Yet, it seems his anger, and those who would agree is either misdirected or self-agitated. Look at what he has to say about the conventional wisdom on Wikipedia:

Let me bring the discussion down to a brass tack. If you read anything about Web 2.0, you'll inevitably find praise heaped upon Wikipedia as a glorious manifestation of "the age of participation." Wikipedia is an open-source encyclopedia; anyone who wants to contribute can add an entry or edit an existing one.

Really? Inevitably find praise...Wikipedia is almost universally unacceptable as a valid source for papers written for a high school or college level paper. Wikipedia is often mocked for its gloriously wrong information. Vandalizers and bad jokes put on Wikipedia have their own page on Wikipedia. I don't think there is the universal praise that Mr. Carr seems to be in such a bind about, I think it is a straw-man, a red herring. Moreover Wikipedia is not great as a primary source, but it is great in nailing down information that is supposedly well-known or canonical for a particular subject. Furthermore, many of the better edited pages have links to more authoritative sources, which are generally interesting and helpful.

What seems to be main argument here is that the Web 2.0 is undermining traditional media and traditional media's opportunity for making money, by overloading individuals' bandwidth for information, entertainment, news, arts, and culture.The traditional media outlets necessarily present better, more polished information that is independently researched, peer-reviewed, fact-checked, edited for grammatical and stylistic errors, marketed, etc...While, on the Web 2.0 side every, Tom, Dick, Harry, and Cindy (can't forget about Cindy) can put up whatever he or she feels like on the Internet, and it suddenly gains authoritative valence. However, the argument that seems so interesting for those that would bash the Web 2.0 is that relatively few people actually do those things. Some of the statistics presented in the book and on Mr. Carr's website claim that relatively few users, through Google Bombing and other related strategies have monopolized the blogosphere, and that individuals with no credentials are given extremely wide discretionary powers to decide what goes on major websites like Digg.com or Wikipedia. Isn't this exactly the sort of argument that was initially levied against big media a few years back, wasn't it maintained that relatively few companies had control of an overwhelming majority of the media outlets currently accessible, and that it would be the Internet that would break this hegemony. Second, this rhetoric is not functionally different from Francis Bacon's criticism of the Idol of the Marketplace in his masterwork Novum Organum. That there is the interaction between the free association of men, which leads to a confusing of language is a well-rehearsed argument. Yet, the false learning and sophistry from supposed wise men to which the masses are to accept since they are the ones with the degrees, pedigrees, and copy editors, well Bacon has an Idol for them too.

What I find intriguing about these sorts of attack is that it is directed toward their ostensible target audience. I started hearing these rumblings from the media industry, when the Atlanta-Journal Constitution decided to discontinue their book review section. There is some suggestion that this was due to the influx of amateur book reviewers on the web cutting off advertising dollars from the print media. There was some backlash to this, and I think for the first time, those in the traditional media formats felt genuinely threatened and afraid for their welfares from a bunch of philistine Internet blog-fiends. But those philistines, those amateur book-reviewers are the ones most likely to pick up a copy of the Atlanta-Journal Constitution and read the section. Book-reviews on blogs are not so ubiquitous as to not avoid being seen. One may suggest it is only one click away; nevertheless, it is still one click away. Most people who aren't looking for book reviews don't find them.

Finally, the claim that those on the Internet posting their random musings, have unchecked biases and hidden or not so hidden agendas is in danger of politicizing and relativizing all forms of media is also a common complaint. That genie won't go back into that bottle, if Richard Rorty (may he find his liberal utopia and final vocabulary in the sky) has taught us anything is that this is just a debate between two different sets of vocabularies the one of the amateur and the one of the professional. No one has claim on Truth, everyone has claim to truths. Whining about the absent moral compass and the lack of a desire for objectivity of some bloggers which will lead to a cannibalizing of culture, is clearly a case of the "lady doth protest too much."

Though I don't want to, I can't help but see a residuum of truth to their position, as transparently self-serving and unimaginative as it is. In Herman Hesse's outstanding The Glass-Bead Game, the scholars of Castilia are rather repulsed by a previous Age of culture called the Age of Feuilleton, the word comes from the French diminutive for leaf or book. In this age sensationalist, cute journalism, cultural criticism and the arts replaced serious reading and close reflection. It occurs at the end of the 20th century, to which the predecessors of the monks of the Glass-Bead game flee in order to reestablish order and proper intellectual edification. This age led to decadence and superficiality to such a degree that there was a massive breakdown in culture and chaos ensued. Though the action in the novel takes place sometime after this age; the concern over such an age is well articulated. I can't help but think that there is some resonance with the warning that Hesse is obviously giving us and the sort of pleas that books like the Cult of the Amateur are intimating. I am not sure if such a warning is representative of plain unadulterated cultural elitism, or is their something genuinely more at stake. What is culture other than the sum of its participants? Can we really assess some type of moral imperative to impugn onto Culture in this day of relativism and postmodern antipathy towards Meta-narratives?

Or is this series of condemnations, just like the ones of 1277 but this time it is not a concern of double-truths being promulgated but double-authorities being established? That in fact it is the Church of the Professional which is launching its own inquisition against the heresies and blasphemies of the Cult of the Amateur. Operators are standing by.

Standing on the dance floor surrounded by the din of the Wednesday night bar crowd and staring blankly into spaces unfamiliar and faces unreachable, I noticed that Late Night with Conan O'Brien was on. His guest that evening was

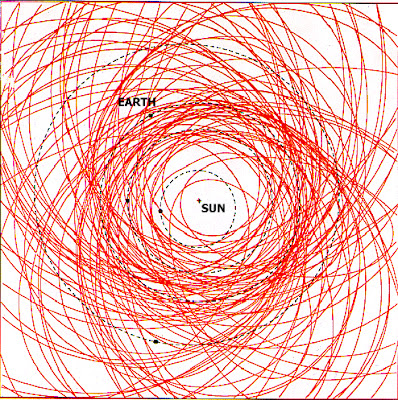

Standing on the dance floor surrounded by the din of the Wednesday night bar crowd and staring blankly into spaces unfamiliar and faces unreachable, I noticed that Late Night with Conan O'Brien was on. His guest that evening was  has been devoted to discovery, tracking and assessment of these objects. The graph to the right shows the orbits of the terrestrial planets along with the orbits of the 100 nearest-to-Earth objects. The Spaceguard, which took its name from a similarly tasked research body in the Arthur C. Clarke novel,

has been devoted to discovery, tracking and assessment of these objects. The graph to the right shows the orbits of the terrestrial planets along with the orbits of the 100 nearest-to-Earth objects. The Spaceguard, which took its name from a similarly tasked research body in the Arthur C. Clarke novel,

Newspapers out of Scotland

Newspapers out of Scotland  Pictured below demonstrating his famed Camel Clutch on an unsuspecting stockbroker, no doubt trying to procure funds for "charity" organizations, he has long had sympathies for the anti-US stance held by Iran. Though he was recently inducted into the Hall of Fame by longtime rival Sergeant Slaughter, interestingly enough, on a June 18th, 2007 episode of "Monday Night RAW," the Sheik requested of Jonathan Coachmen, a representative of WWE and an associate of Mr. McMahon's as well, that he be offered a segment on the show. Coachmen implied that he thought the idea was interesting and would take it under consideration. Perhaps this segment is payment for services rendered on behalf of Mr. McMahon for certain covert overseas operations. A further inquiry should soon be underway.

Pictured below demonstrating his famed Camel Clutch on an unsuspecting stockbroker, no doubt trying to procure funds for "charity" organizations, he has long had sympathies for the anti-US stance held by Iran. Though he was recently inducted into the Hall of Fame by longtime rival Sergeant Slaughter, interestingly enough, on a June 18th, 2007 episode of "Monday Night RAW," the Sheik requested of Jonathan Coachmen, a representative of WWE and an associate of Mr. McMahon's as well, that he be offered a segment on the show. Coachmen implied that he thought the idea was interesting and would take it under consideration. Perhaps this segment is payment for services rendered on behalf of Mr. McMahon for certain covert overseas operations. A further inquiry should soon be underway.